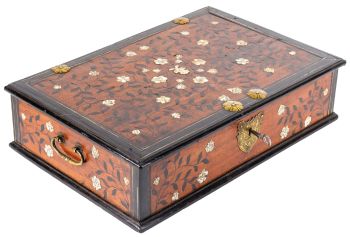

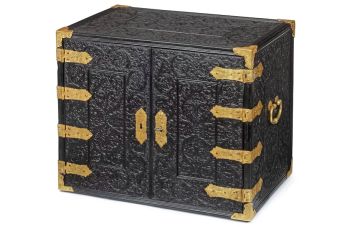

A magnificent pair of Spanish-colonial Viceregal Peruvian mother-of-pearl inlaid bureau-cabinets Vic 1720 - 1760

Artista Desconhecido

PérolaMadrepérola

213 ⨯ 115 ⨯ 52 cm

Preço em pedido

Zebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

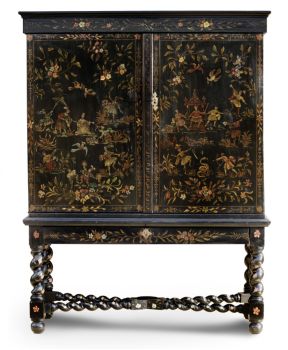

- Sobre arteA magnificent pair of Spanish-colonial Viceregal Peruvian mother-of-pearl inlaid bureau-cabinets

Viceroyalty of Peru, Lima, 18th century, circa 1720-1760

Each with a moulded giltwood cornice and on a foliate carved giltwood base, possibly later and English. The cabinets, with silver mounts, are made of cedar, overall inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The interior is veneered with teak, American crabwood, Gele kabbes, and boxwood.

H. 213 x W. 115 x D. 52.5 cm (each)

Provenance:

Noble collection, United Kingdom; thence by descent

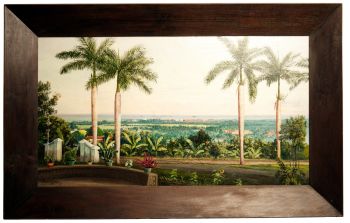

These spectacular bureau-cabinets are part of a fascinating production of decorative art and furniture from Lima, the affluent capital of the Spanish Vice-Royalty of Peru. Included are mother-of-pearl covered altarpieces, lecterns, caskets, boxes, tables, coffers, cabinets, and presumably the rarest: impressive bureaux such as the present pair. They are exquisite material examples of cultural cross-pollination in South and Central America, bridging multiple influences from Asia and Europe in a result that is both visually and historically impactful.

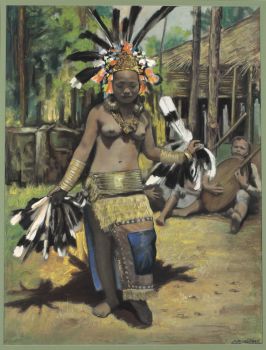

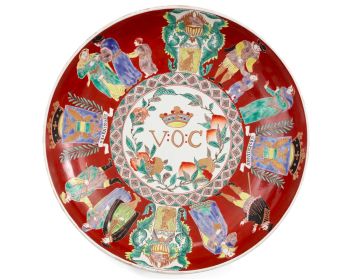

Indian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese and Arabian influence

This pair of cabinets is especially appealing for its shimmering surface of mother-of-pearl veneer, which was described as enconchado in inventories. It has as precursors the ‘Indo-Portuguese’ caskets, jugs and bowls, often silver mounted, produced in the Indian region of Gujarat in the 16th and early 17th centuries. These were shipped from Goa, the Portuguese colonial trade post on the west coast of India, to Portugal intended for the greatest monasteries, cathedrals and palaces of the country. Already in 16th century these lustrous Gujarati caskets, with nacre veneer fastened with silver nails in a fish-scale pattern were considered so precious in Europe that they were classified as jewellery in the inventories of royal collections and even nowadays they still are regarded as the most sought after works of art.

The Portuguese used the shimmering treasures from Gujarat as diplomatic gifts, which is how they ended up in the famous Habsburger kunstkammers of Vienna and Dresden. More important in this case are the reliquary caskets and other religious wares that ended up in collections of several Spanish monasteries and churches, as well as the games- boards and table-tops that were centrepieces in the homes of the most notable Spaniards.

With the establishment of more Portuguese trade routes within Asia, the Indian mother-of-pearl objects influenced the Japanese lacquer production. In large numbers the Portuguese ordered lacquerware for the purpose of being exported to Europe or big colonial cities like Spanish Manilla. The Spanish Manilla Galleon trade brought these objects to South America and, thus, to the Viceroyalty of Peru. It didn’t take long before there was a true rage for furniture decorated with nacre. However, the Portuguese controlled the market as they had monopolized access to the ports where the pieces could be ordered, such as Gujarat and Japan. Paying high prices, the Spaniards exported the goods to the Viceroyalties, where they enjoyed enormous popularity amongst the affluent class, particularly in Mexico and Peru. It wouldn’t be long before the Spanish brought Asian craftsmen to South America to produce these iridescent works of art themselves.

By the 18th century, the regular flow of the Manilla galleons from Manilla to Acapulco introduced an enormous quantity of Asian luxury items in both the Vice-Royalties of New Spain and Peru, with immediate and apparent influences on the local craftsmen and taste of the elites. The Asian influences in technique and motifs arrived from goods and through Asian craftsmen. Japanese and Chinese workers brought the techniques of inlaying materials (lacquer, a sort of gum or tree sap called mastic, wood, tortoiseshell, and much more) with mother-of-pearl. Arabs, who had to ‘convert’ to Christianism before they were allowed to immigrate, brought in Múdejar skills and their distinctive abstract approach to ornament without the imagery of animals or humans, as stated in the Quran. These cabinetmakers with all sorts of backgrounds in Mexico and Peru started to produce the finest inlaid and or veneered furniture and objects in the 17th and 18th centuries in their own style – each influenced by various available techniques and motifs. The most popular among the buyers would eventually become dominant.

Reflecting the syncretic nature of the present bureau- cabinets, the floral design of the mother-of-pearl veneers appears to have been inspired by ancient Korean designs from the Joseon or Chosõn Dynasty, seen in porcelain

and objects with mother-of-pearl inlays on wood grounds. These designs are also seen in another Peruvian technique, which uses mother-of-pearl inlays on a tortoiseshell ground. However, most Far Eastern mother-of-pearl techniques find their origins in Korea.

European influence

The most visible influence is the European. First of all, the form of these bureau-cabinets was based on English

prototypes, which were made and exported to the Iberian peninsula throughout the 18th century, often in pairs, becoming part of the vocabulary of Iberian aristocratic interiors – and soon produced by the Iberians too. The English production of cabinets in pairs is only seen for the export market, and it is interesting to see how this taste was carried out across the Atlantic Ocean. They were listed in local inventories as ‘buró-libreria’ or ‘escritorio-papelera’ and are frequently described as ‘a la Inglesa’.(1)

Secondly, the interiors of the upper parts and the inside of the fall-front desk, using local hardwoods, present a lozenge pattern, which originates in 16th and early 17th- century Southern Netherlandish and, therefore, Spanish furniture designs. A product of the former Habsburger global domination and cultural flow between their territories.

The artisans

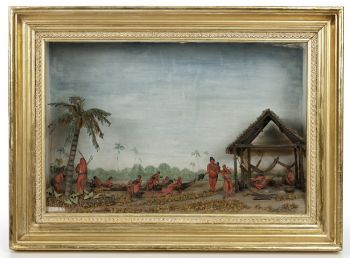

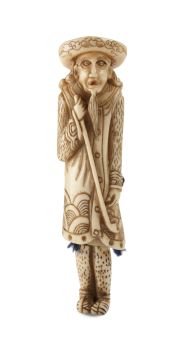

Spanish ‘government’, (naval) military officials and soldiers, tradesmen, craftsmen, and priests and monks of various religious orders moved to these far-away destinations as representatives of the Spanish Crown. They all carried

out their important ‘evangelising mission’, justifying their presence. The murder, war and looting of the land’s riches were justified, too, in this matter. Notably, people from other parts of the Spanish colonial empire also arrived. There is evidence of migration from Japan to the coasts of Peru in the 17th century. There is proof that Japanese people settled in Lima around 1607. “The 1613 census, carried out in Lima to register ‘Indians’ (Asians were considered as such) revealed a total of twenty Japanese, who were called 'japonex'. The Japanese who arrived in Peru during this period came from the Philippine Islands. At that time, Japan had close ties with Manilla. Some of them had been enslaved by the Portuguese [...] in Lima they became free. Some had been born in Japan, but others, in Goa (India) of Japanese parents or grandparents. The Japanese who arrived in Peru during this period came from the Philippine Islands. At that time, Japan had close ties with Manilla [...]. Some of them had been enslaved by the Portuguese [...] ...in Lima, they became free. Some had been born in Japan, but others, in Goa (India), were of Japanese parents or grandparents.”(2)

It is nearly certain that, over time, some of them would become craftsmen and carpenters trained in the decorative technique of lacquer, which was developed in Japan. Later, they would pass their skills to local Spanish (of mixed descent), Creole, Arabian and indigenous or native craftsmen, who, in turn, would add their motifs and designs to the objects. In the Peña Prado cabinet, the strong influence of Japanese Namban lacquer can be seen. Such motifs are already found in 13th- 16th-century Chinese and Korean lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Probably recognised by the Portuguese from the Moresque motifs in their home country, and thus ordered this kind of motifs.

Style

Comparing the Peruvian inlaid furniture with other pieces produced in Latin America, Peter Gjurinovic Canevaro states “...they are dramatically different from those made in Peru. Thus, it can be shown that, due to an Eastern influence, these inlaid pieces were developed with their own characteristics in their respective countries.” For the Peruvian pieces, later, strictly Baroque ornamentation was selected to convey a strong feeling of opulence; the pieces also featured a distribution of elements alien to the Japanese style, which was slowly left behind. The profuse decoration reveals the horror vacui characteristic of these kinds of pieces.

A preliminary sketch was drawn by craftsmen trained in the Namban lacquer technique, which they combined with their artistic background of both Mudejar and indigenous roots, thus resulting in truly Peruvian pieces

of furniture rich in cultural symbiosis, like the present pair of cabinets. It is worth noting the natural inclination of the Arab craftsmen living in the Viceroyalty of Peru to abstract motifs, which were critical to their style and the distinctiveness of their way of viewing art. Those motifs are also seen in the geometric transformation of ornaments, friezes, and ribbons, which repeatedly appear, reflecting a Spanish influence typical of Spanish-

Mudejar furniture.

Mother-of-pearl only

Within the various styles nurturing inlaid furniture production, it is necessary to emphasise the technique consisting of the almost exclusive use of mother-of-pearl and the application of stylised decorative schemes within a near-invisible or very thin wood or tortoiseshell filet. This type of finishing should be associated with the one seen in the production of caskets veneered with mother-of-pearl from Gujarat, India. It can be assumed that this source of inspiration reached the west coast of the Americas or even through Portuguese-Spanish connections on the Iberian peninsula.

In the Sala de los Tratados of Palacio de Torre Tagle, in Lima, there is an example of a fully mother-of-pearl veneered bureau-cabinet whose quality is just as remarkable as the pair presented by us. It was a generous donation made in 1978 by Doña Teresa Blondet de Cisneros in memory of her husband, Don Manuel Cisneros Sánchez, who had acquired it. The piece alludes to the Rococo style enthusiastically adopted in Lima under Bourbon’s influence. However, this cabinet is crowned by a fretted cresting, with a double-headed eagle at the centre, flanked by fretted rinceaux on the front and the side combs.

Technique

The incredibly time-consuming technique is most likely an important reason for the rarity of these bureau cabinets. The number of mother-of-pearl pieces used in such a bureau is in the region of 7000, each made from an individual section of shell, sawn delicately, ground smooth and then sawn again to the shape of a paper template, after which it was grounded again to the desired thickness showing the perfect lustre.

It probably took over fourty minutes to work on each tiny piece. One should not forget that the extreme fragility of a fraction of a millimetre thick piece would only result in a usable piece about one in ten tries.(3) Due to the similarity of method and designs applied, it can be suggested with near certainty that all of these cabinets and related smaller pieces of furniture come from the same workshop or interrelated workshops, which unfortunately has or have not yet been identified.

The only surviving pair?

This appears to be the only surviving pair within the small group of Viceregal fully mother-of-pearl veneered bureau- cabinets. The ones known today are an example in the Palacio Torre de Tagle, today the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lima, with a crest showing the Habsburg double eagle; another in an important private collection Mexico, one with an openwork crest in the collections of the V&A Museum, London (inv.no. W.3-1943); one in a private collection in Italy; and another example, in Rough Point House Museum, Newport, the home of the collector and philanthropist Doris Duke (inv. no. 1999.437).

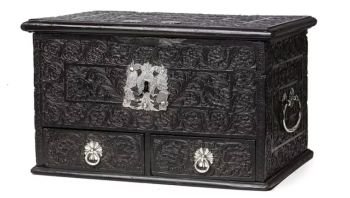

In the Sala Buenos Aires Capital del Virreinato, at the Museo de Arte Hispanoamericano Isaac Fernández Blanco, in the city of Buenos Aires, there is a coffer which was part of the collection of architect Martin Noel, a great collector

of American colonial art who spent long periods in Lima throughout the 20th century. Here he built what would later become the Argentine Embassy in Peru. The technical features of this coffer are similar to those of the bureau- cabinets. This coffer has an upper lid, a front lock and an aside drawer. It rests on four claw-shaped legs made from engraved silver. The external decoration, with a distinct Japanese influence, was the result of applying the inlay technique using almost white tones. The piece has flat surfaces covered with a profusion of scales made from nacre fragments fileted with light-coloured wood – just as in the cabinets.

The pair presented here comprises an exciting discovery, a remarkable example of global cross-cultural material culture, reflecting the epitome of elite taste of the exuberant Viceregal societies in Spanish-colonial America. Lastly, they are in remarkably good condition, so one can conclude that because of their high value and luxury status at the time, these pieces were treated as art objects – and were solely used for the most expensive goods used in the house, such as crystal, glassware, silver or gold tableware, porcelain and linens.

Sources:

1 Gabriela Germana Róquez, “El mueble en el Perú en el siglo XVIII: estilos, gustos y costumbres de la elite colonial”, in: Anales del Museo de America, vol. 16, 2008, p. 198

2 Mary Fukumoto, “Migración Japonesa al Perú”, in: Boletin de Lima, 20, vol. XX, 1998, no. 114, p. 81

3 https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/0109845/desk-and-bookcase-unknown/ - Sobre artista

Pode acontecer que um artista ou criador seja desconhecido.

Algumas obras não devem ser determinadas por quem são feitas ou são feitas por (um grupo de) artesãos. Exemplos são estátuas dos tempos antigos, móveis, espelhos ou assinaturas que não são claras ou legíveis, mas também algumas obras não são assinadas.

Além disso, você pode encontrar a seguinte descrição:

•"Atribuído a …." Na opinião deles, provavelmente uma obra do artista, pelo menos em parte

• “Estúdio de…” ou “Oficina de” Em sua opinião um trabalho executado no estúdio ou oficina do artista, possivelmente sob sua supervisão

• "Círculo de ..." Na opinião deles, uma obra da época do artista mostrando sua influência, intimamente associada ao artista, mas não necessariamente seu aluno

•“Estilo de…” ou “Seguidor de…” Na opinião deles, um trabalho executado no estilo do artista, mas não necessariamente por um aluno; pode ser contemporâneo ou quase contemporâneo

• "Maneira de ..." Na opinião deles, uma obra no estilo do artista, mas de data posterior

•"Depois …." Na opinião deles uma cópia (de qualquer data) de uma obra do artista

• “Assinado…”, “Datado…” ou “Inscrito” Na opinião deles, a obra foi assinada/datada/inscrita pelo artista. A adição de um ponto de interrogação indica um elemento de dúvida

• "Com assinatura ….”, “Com data ….”, “Com inscrição ….” ou “Tem assinatura/data/inscrição” na opinião deles a assinatura/data/inscrição foi adicionada por outra pessoa que não o artista

Você está interessado em comprar esta obra de arte?

Artwork details

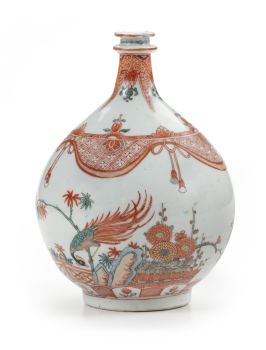

Related artworks

- 1 - 4 / 12

Artista Desconhecido

Japanese transition-style lacquer coffer 1640 - 1650

Preço em pedidoZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24 Com curadoria de

Com curadoria deDanny Bree

1 - 4 / 24- 1 - 4 / 24

- 1 - 4 / 12